Besotted Brain Blunders

Featured Article

The pair sat in my office: AJ, slumped in an overstuffed chair, his wife BJ (they were definitely into acronyms) rigid on a stool.

After introductions, I asked what they wanted to discuss. AJ looked at BJ. She looked back at him.

“AJ has a disease,” BJ said finally. “It’s ruining our lives.”

“And BJ enables my disease,” AJ retorted.

“In a couple of sentences,” I said to AJ, “tell me the issue.”

Clearing his throat, AJ looked out the window, tried to squirm but his 350 pounds packed his chair to overflowing. Finally he said, “At one time or another during our 25 years of marriage I have been addicted to sex, tobacco, booze, television—and now food. I eat all the time. It’s escalated from an avocation to a vocation. I just want to feel better.”

“Of course you do,” I replied. “The brain itself wants to feel better. The problem comes when you and your brain develop strategies to feel better quickly rather than creating and maintaining a healthy lifestyle: physically, emotionally, mentally, spiritually, sexually, socially, and you name it. The strategies can quickly escalate into addictive behaviors as the brain learns to go for the fast dopamine thrill. Problem is that each thrill lasts only for a short time.” AJ nodded.

I looked at BJ. “Please explain the enabling issue,” I said.

BJ sighed dramatically. “What am I supposed to do? AJ snacks continually, eats a quart of ice cream every night, complains bitterly if fridge and freezer are not stocked with all his favorites… It’s easier to keep them stocked than listen to him whine—and then he blames me. Whines and blames. I do not understand the brain and addiction.”

“Whining is just anger squeezing out through a very small opening,” I replied. “Blaming is an attempt to displace some of the discomfort you feel onto someone else. It provides a momentary illusion of feeling better, although it never solves anything.

“So what are my options?” AJ asked, a belligerent tone creeping into his voice. “Bariatric surgery for stomach stapling?”

“That is an option,” I replied, “but it’s a drastic surgery and the problem begins in your brain, not in your stomach, so many gain back what they lost. That’s the problem with a besotted brain: the biggest cure for one addictive behavior is another one. You may want to evaluate your self-medication habits.”

AJ shrugging. “Guess it’s in my genes. Addictions run through our generational family like water through the Grand Canyon.”

“That sounds like an excuse,” I replied. “Your brain can only do what it thinks it can do and you are the one who tells it what it can do. Yes, genetic and epigenetic inheritances do play a part, but estimates are that seventy percent of how well and how long you live is in your own hands. If your brain believes there is no problem with your lifestyle, it will continue to prompt you to do whatever makes you feel better right now, giving little if any thought to how it will impact your future health and longevity.”

“And self-medication?” asked AJ, changing the subject. “I do not do drugs!”

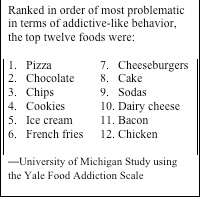

“What is your definition of a drug? The brain can use almost anything as a ‘drug’ as long as it releases dopamine and makes you feel better. Metaphorically think of your brain, not as a pot of gold (although it is likely the ultimate pot of gold), but rather as both a pot of chemical stew and as a pharmacy. As chef, you self-medicate through what you ingest. As pharmacist, you alter brain chemistry through behaviors or thoughts that release brain chemicals that change the way you feel.” I handed each a list of the top twelve foods ranked in order of most problematic in terms of addictive-like behavior.

gold (although it is likely the ultimate pot of gold), but rather as both a pot of chemical stew and as a pharmacy. As chef, you self-medicate through what you ingest. As pharmacist, you alter brain chemistry through behaviors or thoughts that release brain chemicals that change the way you feel.” I handed each a list of the top twelve foods ranked in order of most problematic in terms of addictive-like behavior.

“Lord have mercy!” AJ groaned. “I love all of those. Eat most of ‘em every day!”

“That’s why I say you’ve got a ‘disease,’” BJ said emphatically. “A disease changes your brain, right?”

“Sometimes a disease changes your brain,” I replied. “Sometimes what goes on in your brain contributes to the development of disease. Either way it’s not the highway to high-level-healthiness.”

“But . . . “ began AJ, but BJ interrupted. “He’s been involved with so many addictive behaviors and been to so many programs—they’re all so different—that we’re totally confused.”

“Almost anything can turn into an addictive behavior and while the boundary parameters may vary, the basic recovery strategies are very similar,” I explained, “because addictive behaviors all trigger the Brain Reward System or BRS.”

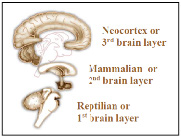

Getting out a model, I explained the triune brain with its three basic brain layers along with an easy way to remember each in order. Look at your left wrist. It represents the reptilian or 1st brain layer—which contains repetitive routines that often kick in automatically unless you make a different choice. It processes primarily the present tense (right here, right now). Form your left hand into a fist. That represents the mammalian or 2nd brain layer—which contains major functions related to the BRS. It processes both the present and past. Cup your other hand over your fist and picture that as the neocortex or 3rd brain layer—which contains the function of conscious thought and can process present, past, and future tense.

layer—which contains repetitive routines that often kick in automatically unless you make a different choice. It processes primarily the present tense (right here, right now). Form your left hand into a fist. That represents the mammalian or 2nd brain layer—which contains major functions related to the BRS. It processes both the present and past. Cup your other hand over your fist and picture that as the neocortex or 3rd brain layer—which contains the function of conscious thought and can process present, past, and future tense.

When the brain wants to feel better, it tends to look for some person, place, substance, or thing to trigger the release of dopamine, the feel-better chemical, 50% of which is in your brain and the rest in your gut. When it begins to feel better, the BRS pays attention. The next time the brain wants to feel better, the BRS pushes you to do whatever released dopamine last time. Before very long, you can develop a very strong habit that can move on to an addictive behavior. It’s not that it is absolutely impossible to control an addictive behavior, but eventually the behavior that triggers the BRS becomes so strong that most people just give up trying. Even the anticipation of doing something that makes your brain feel better can trigger the release of dopamine.

“Oh my goodness,” BJ and AJ said in unison and AJ continued. “How come no one ever explained it like this before? I get it! I feel bad; my BRS pushes me to do what made me feel better last time; I do the behavior and feel better. Next time I feel bad, the cycle repeats. Wow!”

“This is now the age of the brain,” I replied. “Some of this wasn’t even known until quite recently. Addictive behaviors are complex, and yet at their core the process is relatively simple. No need to make it more complicated than necessary.”

BJ looked at her watch. “So next week we’re talking about . . . what?”

“Busting Bad Behaviors,” I said. They left actually smiling.

Arlene R. Taylor PhD

Realizations Inc

[Editor’s note: This is the Part One of Dr. Taylor’s two-part series on the addicted brain. Part Two will appear in the November-December issue of the Journey to Life]