Sugar and Health

Is There A Sweet Spot?

Contributed by Maggie Collins, MPH, RDN, CDCES, DipACLM

We are born naturally inclined to like sweet foods. The food industry has picked up on that and flooded our surroundings with products loaded with sugar. But what is the impact of habitual intake of sugary foods on our health? Are all sugars harmful? Does the Bible have anything to say about that? Is it possible to design a healthy dessert? What are the healthiest replacements for sugar?

What is Sugar

Sugar is a basic unit that forms all types of carbohydrates present in fruits, vegetables, milk (including human milk), and starchy foods (such as grains, legumes, starchy vegetables, nuts, and seeds). When these foods are digested, the different types of carbohydrates end up as the most basic sugar units: glucose, galactose, or fructose [1]. For a deeper understanding on carbohydrates in general please read the article Making Peace with Carbohydrates.

Different Types of Sugar

- Naturally Occurring Sugars are sugars contained within the cell walls of plants (fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains, nuts, and seeds) and in milk (including human milk).

- Added Sugars refer to sugars and syrups that are added to foods during processing or preparation [1]. Examples are: white sugar, brown sugar, raw sugar, honey, molasses, maple syrup, coconut sugar, date sugar, corn syrup, corn-syrup solids, high-fructose corn syrup, malt syrup, pancake syrup, fructose sweetener, liquid fructose, agave, anhydrous dextrose, and crystal dextrose.

- Sugar Alcohols (aka polyols) refer to carbohydrates with a hybrid chemical structure that partially looks like sugar and partially looks like alcohol. Despite the “alcohol” part of the name, they do not contain ethanol as in alcoholic beverages. Examples are: sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, maltitol, maltitol syrup, lactitol, erythritol, isomalt and hydrogenated starch hydrolysates. These sugars partially resist digestion, so their calorie content ranges from 1.5 to 3 calories per gram compared to 4 calories per gram for other sugars. This form of sugar can be naturally occurring in fruits and vegetables, but it can also be manufactured from sucrose (table sugar), glucose, and different types of starch to be used in processed foods as a sweetener, bulking agent, to achieve a certain mouthfeel, to retain moisture in the product, and to prevent browning that can occur during heating.

- Sugar Substitutes (aka nonnutritive high-intensity sweeteners or artificial sweeteners) refer to chemically or physically manipulated sweeteners that are many times sweeter than sugar while being zero- or low-calorie. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the following nonnutritive sweeteners: acesulfame-K, advantame, aspartame, monk fruit, neotame, saccharin, sucralose and stevia.[2]

Functions of Sugar

The digestion of carbohydrates in the body causes the breakdown of large molecules into the most basic sugar molecules called glucose, fructose, and galactose. Glucose is the most abundant sugar and the one the body relies on as a primary source of energy [3, 4].

Added-sugars are used as sweeteners not only to increase the palatability of foods, but also to achieve certain textures, body, viscosity, and appearance such as the browning capacity. Sugars can also be used for food preservation.

The Health Impact of Different Types of Sugar

Different types of sugar produce different physiological responses in the body.

Naturally occurring sugars

The first type of food most of us are exposed to in life – breast milk – has a significant amount of naturally occurring sugar (lactose), even more so than cow’s milk. [5] This probably contributes to our innate preference for the sweet taste, and it is a characteristic certainly designed by God for a reason, to make sure babies will desire to consume enough of this food to grow and develop properly.

Other naturally occurring sugars, in the context of whole plant foods, such as fruits, are released slowly, due to the presence of water and fiber. In addition, fruits contain vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and phytochemicals which have all been identified as health promoting. Thus, even though fruits can be quite sweet, they have been associated with a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes; and for those who already have diabetes, they are associated with preventing diabetes complications and lowering all-cause mortality[6-9]. Fruits have also been associated with lower body weight and have been used in dietary approaches to prevent, manage or reverse obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cognitive impairment later in life [10-13]. The American Institute for Cancer Research states that fruits lower the risk for many cancers [14].

Added Sugars

Foods that contain added-sugars in high amounts such as ultra-processed foods (examples are pastries, baked goods, donuts, frozen desserts, candy bars, cookies, and sweetened beverages) have been associated with asthma, obesity, type-2 diabetes, cancer, gastrointestinal disorders, depression, frailty, cardio-metabolic risk and cardiovascular diseases [15, 16]. For more details on what are ultra-processed foods please refer to the article Making Peace with Carbohydrates.

A classic study published in 1973 measured the effect of the intake of a high-concentration of sugar in the form of 100g of carbohydrates from sucrose, glucose, fructose, honey, or orange juice on the activity of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell from our immune system) of healthy individuals. The individuals tested had to consume this amount all at once after an overnight fast, and had their blood drawn at different time intervals to analyze the neutrophil ability to engulf a certain type of bacteria being tested. To put things into perspective, the amount of sugar tested was equivalent to consuming in one seating six tablespoons of honey, eight tablespoons of sugar, two and a half cans of regular soda, or 1 quart of orange juice. The results showed a reduction of about 50% on the ability of this cell to engulf bacteria 2 hours after the ingestion of those concentrated forms of sugar [17]. This finding lead to the conclusion that when sugar is consumed in large amounts in the form of added-sugar or natural sugar outside the context of the whole fruit (as in the case of the orange juice), it can significantly impair our immune system’s ability to fight infections.

Artificial Sweeteners

Routine consumption of artificial sweeteners has been associated with increases in weight and waist circumference, higher incidence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular events[18]. How can something that does not have calories cause so much damage? There are several proposed mechanisms to explain that. Artificial sweeteners appear to interfere with our gut microbiome, decrease satiety, and alter the way the body process carbohydrates[19]. One study with healthy individuals demonstrated that the calories saved by consuming a sugar-free beverage sweetened with artificial sweeteners were fully compensated throughout the day, and they presented significantly higher blood sugars after the meal following the consumption of that beverage [20].

How Much Sugar Should We Have Per Day?

To better answer this question, it is important to discuss whether sugar is essential to our bodies or not. The only sugar that is essential to our bodies is glucose. To ensure the right amount of glucose is provided for the body to function optimally, the focus should be on consuming a variety of whole food plant-based carbohydrates. For specific amounts on carbohydrates recommended per age and gender refer to the article Making Peace with Carbohydrates.

When it comes to added-sugars, the focus is on limiting excess intake. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans suggests limiting added-sugars to less than 10% of the calories consumed per day, starting at age 2 [1]. Before age 2, the recommendation is to avoid foods and beverages with added-sugar altogether. For an individual eating a 2,000 calorie-diet the limit on the calories coming from added-sugars should be 200 calories. Since each gram of sugar releases 4 calories, those 200 calories would translate to a limit of 50 grams of added-sugar per day. The limitation with this guideline is that one could justify drinking a can of regular soda every day, which contains on average 40 grams of sugar, even though sugar-sweetened beverages have been linked to an increased risk for cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and ultimately premature death [21-25]. For this reason, the American Heart Association recommends a more prudent approach, suggesting limiting added-sugar intake to:

- 9 teaspoons (36 grams) per day for most men

- 6 teaspoons (25 grams) per day for most women and children over 2 [26].

An even more strict approach of completely eliminating the intake of foods high in added-sugars has been suggested to manage or reverse chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [10, 11, 27].

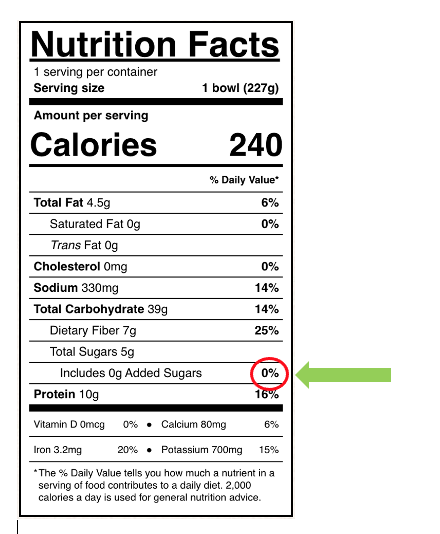

To identify what foods are low or high in added-sugars, refer to the Nutritional label, identify the Serving size for that product, and next look for the % Daily Value (DV) for Added Sugars [28] :

- Products that have 5% or less of the DV for Added Sugars are considered low in added-sugars;

- Products that have 20% or more of the DV for Added Sugars are considered high in added-sugars;

- Products that have 6% – 19% of the DV for Added Sugars do not have an official definition.

Does the Bible have Anything to Say about Sugars?

The Bible does not mention the word sugar directly, but it does refer to foods that contain sugar.

- Fruits are without a doubt a health-promoting food group as they were created by God before sin entered the world, were cultivated by His people, and are mentioned as part of the diet in heaven (Genesis 1:29, Exodus 23:10, Revelation 22:2).

- Manna is described as having the taste of wafers made with honey (Exodus 16:31), so it indicates it had a somewhat sweet taste and were designed as the perfect food to sustain God’s people while sojourning in the desert.

- Honey is mentioned as something good when eaten in moderation (Proverbs 24:13, Proverbs 25:16, Proverbs 25:27).

Although the Bible does not address every single article of food we consume in our times, when it comes to making decision about sugar-rich foods we can apply the biblical principles of giving preference to whole plant-based foods, limiting the use of concentrated sugars such as honey to a small amount, and eating foods that will not destroy our bodies (I Corinthians 3:16, 17; I Corinthians 9:24-27; I Corinthians 10:31; Galatians 5:22, 23).

The Seventh-Day Adventist Health Message Approach to Dealing With Sugar

Ellen White, one of the founders of the Adventist Church, warns that the free use of sugar can be a cause of diseases (Counsels on Diet and Foods, 196.4), but her counsel makes room for occasional simple desserts like simple pies, rice pudding, and plain cakes (Counsels on Diet and Foods, 334.1; 333.5).

Fruits, in several forms (fresh, dried, homemade juice, and canned at home) are promoted in her writings but fresh fruit is placed on the top in terms of health benefits (The Ministry of Healing, 299; Counsels on Diet and Foods, 96.1; 309.3; 333.2; 436.4; 437.1)

She also mentions using a little sugar when canning fruits for the winter, for the purpose of assisting with preservation (The Ministry of Healing, 229).

The use of honey was already explicitly approved in the Bible, so she doesn’t seem to take much time on the use of honey as an article of food, but mentions that she used boiled honey mixed with eucalyptus oil as a natural remedy for cough and difficulties with her throat (Selected Messages, Vol 2, 301.1)

The following quote represents a good summary of The Seventh-Day Adventist health message on sugar:

Let those who advocate health reform strive earnestly to make it all that they claim it is. Let them discard everything detrimental to health. Use simple, wholesome food. Fruit is excellent, and saves much cooking. Discard rich pastries, cakes, desserts, and other dishes prepared to tempt the appetite. Eat fewer kinds of food at one meal, and eat with thanksgiving.

Letter 135, 1902

Summary

Sugar is not bad in and of itself, as sugar comes in many forms, so when discussing the impact of sugar on health we need to be specific on what type of sugar we are talking about. It is not bad to enjoy the sweet taste either as God designed it to be very abundant in the first food most of us are exposed to (breast milk) and in the delicious fruits he created. Therefore, when it comes to sugar and health, the sweet spot is found favoring the whole foods that have naturally occurring sugar, especially fruits as they are packed with so much nutrition that by eating them we are reducing the risk of several chronic conditions.

The decision on the frequency of an occasional dessert or treat is for each individual to make, taking into consideration their health status, physical activity level, and personal goals. Ideally those desserts and treats should be made from whole ingredients and sweetened with dried fruit, fruit juice, apple sauce, or with a low amount of added-sugars. There are several websites that promote a whole food plant-based diet with recipes already modified to please the taste while preserving our health.

As with any dietary choice, the goal is to continue to progress towards the ideal of enjoying the healthy foods God created for us in their unprocessed or minimally processed forms, not forgetting an equally important application of sweetness which is that we Christians are called to be sweet and patient with those that may see these matters differently than us.

Pleasant words are like a honeycomb,

Sweetness to the soul and health to the bones.Proverbs 16:24

References

- Agriculture., U.S.D.o.H.a.H.S.a.U.S.D.o. 2020 – 2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.9th Edition. 2020 December 2020; Available from: www.dietaryguidelines.gov/.

- (FDA)., F.a.D.A., Additional Information about High-Intensity Sweeteners Permitted for Use in Food in the United States. 2018.

- Levin, R.J., Digestion and absorption of carbohydrates–from molecules and membranes to humans. Am J Clin Nutr, 1994. 59(3 Suppl): p. 690s-698s.

- Southgate, D.A., Digestion and metabolism of sugars. Am J Clin Nutr, 1995. 62(1 Suppl): p. 203S-210S; discussion 211S.

- Ballard, O. and A.L. Morrow, Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatric clinics of North America, 2013. 60(1): p. 49-74.

- Christensen, A.S., et al., Effect of fruit restriction on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes – a randomized trial. Nutrition Journal, 2013. 12(1): p. 29.

- Li, M., et al., Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ Open, 2014. 4(11): p. e005497.

- Du, H., et al., Fresh fruit consumption in relation to incident diabetes and diabetic vascular complications: A 7-y prospective study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. PLoS Med, 2017. 14(4): p. e1002279.

- Hung, H.C., et al., Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2004. 96(21): p. 1577-84.

- Wright, N., et al., The BROAD study: A randomised controlled trial using a whole food plant-based diet in the community for obesity, ischaemic heart disease or diabetes. Nutr Diabetes, 2017. 7(3): p. e256.

- Esselstyn, C.B., Jr., Resolving the Coronary Artery Disease Epidemic Through Plant-Based Nutrition. Prev Cardiol, 2001. 4(4): p. 171-177.

- Sharma, S.P., et al., Paradoxical Effects of Fruit on Obesity. Nutrients, 2016. 8(10): p. 633.

- Wu, J., et al., Dietary pattern in midlife and cognitive impairment in late life: a prospective study in Chinese adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2019. 110(4): p. 912-920.

- (AICR)., A.I.f.C.R. AICR’s Foods that Fight Cancer™. 06/03/21]; Available from: https://www.aicr.org/cancer-prevention/food-facts/.

- Monteiro, C.A., et al., Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 2019. 22(5): p. 936-941.

- Monteiro, C.A., et al., Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr, 2019. 22(5): p. 936-941.

- Sanchez, A., et al., Role of sugars in human neutrophilic phagocytosis. Am J Clin Nutr, 1973. 26(11): p. 1180-4.

- Azad, M.B., et al., Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. Cmaj, 2017. 189(28): p. E929-e939.

- Pearlman, M., J. Obert, and L. Casey, The Association Between Artificial Sweeteners and Obesity. Curr Gastroenterol Rep, 2017. 19(12): p. 64.

- Tey, S.L., et al., Effects of aspartame-, monk fruit-, stevia- and sucrose-sweetened beverages on postprandial glucose, insulin and energy intake. Int J Obes (Lond), 2017. 41(3): p. 450-457.

- de Koning, L., et al., Sweetened beverage consumption, incident coronary heart disease, and biomarkers of risk in men. Circulation, 2012. 125(14): p. 1735-41, s1.

- Fung, T.T., et al., Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009. 89(4): p. 1037-1042.

- Malik, V.S., et al., Long-Term Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Mortality in US Adults. Circulation, 2019. 139(18): p. 2113-2125.

- Malik, V.S., et al., Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2013. 98(4): p. 1084-1102.

- Malik, V.S., et al., Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2010. 33(11): p. 2477.

- Johnson, R.K., et al., Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2009. 120(11): p. 1011-20.

- Esselstyn, C.B., Jr., et al., A strategy to arrest and reverse coronary artery disease: a 5-year longitudinal study of a single physician’s practice. J Fam Pract, 1995. 41(6): p. 560-8.

- (FDA)., F.a.D.A. How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label. 2020 03/11/2020 06/15/2021]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/how-understand-and-use-nutrition-facts-label.

Leave A Comment