The Truth About Proteins

Contributed by Maggie Collins, MPH, RDN, CDCES, DipACLM

Protein is a nutrient that receives a lot of attention and the food industry loves to highlight it in their products, but do we really need to eat a lot of it for good health? We’ll discuss the scientific evidence on how much protein we should be getting at different stages of life, what are the healthiest sources of protein, and how to ensure protein adequacy when eating a plant-based diet.

This article is part of the Joy of Eating Club resources. Click on the logo to go to the Club page for more resources.

What are proteins?

Proteins are large molecules involved in the building and repair of tissues and many metabolic activities in the body. They are the major structural element for all cells in the body, and are also used to make hormones, enzymes, antibodies, neurotransmitters, and can store and transport nutrients [1].

Proteins are made up of smaller units, called amino acids. There are 20 different types of amino acids that can be combined in different ways to provide all the proteins we need. Some of these amino acids are considered essential because they must be provided in the diet. Others are considered non-essential because the body can make them from other amino acids or other specific substances containing nitrogen. The last group are considered conditionally essential as the body is not able to synthesize them in some circumstances, such as in premature birth, newborns, situations that cause a massive amount of protein losses (eg, after a major injury, major surgery, or suffering severe burn), as well as those suffering from chronic poor dietary intake, chronic intestinal disorders, chronic hepatitis, and other conditions that cause muscle wasting [2-4].

How much protein do we need?

It’s important to include good protein sources in our daily meals. The amount of protein that will meet the needs of the majority of the population at different stages of life is provided by the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) report – a set of reference values to guide the nutrient intake of healthy people, produced by a panel of health experts. Watch our webinar to learn more about Dietary Guidelines for Americans. For most nutrients, including protein, a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is established, which is estimated to cover the needs of 97.5 percent of each age group [3].

Infants have specific needs as well. Experts use the Adequate Intake (AI) instead of the RDA for this age group as it reflects the observed mean protein intake of infants fed predominantly with human (breast) milk. The AI of protein for infants 0-6 months is 1.52 g/Kg body weight/ day and the optimal source of protein during this stage of life is human milk [3].

Recommended Dietary Allowance by Age and Gender

| Age Group | grams/kg body weight/day | grams/day |

|---|---|---|

| Infants (AI) | ||

| 7-12 months | 1.0 | |

| Children (RDA) | ||

| 1-3 years | 1.05 | 13 |

| 4-8 years | 0.95 | 19 |

| 9-13 years | 0.95 | 34 |

| Adolescents (RDA) | ||

| Boys, 14-18 years | 0.85 | 52 |

| Girls, 14-18 years | 0.85 | 46 |

| Adults (RDA) | ||

| Men, 19 years and older | 0.85 | 52 |

| Women, 19 years and older | 0.85 | 46 |

This amounts above need to be adjusted under the following conditions:

- Pregnancy: additional 25g protein/day over pre-pregnancy requirements during the last two trimesters[3]; adjustments may be needed for adolescent pregnancy and for pregnancies supporting the growth of more than one fetus.

- Lactation: additional 25 g protein/day over pre-pregnancy requirements[5];

- Some illnesses, such as liver disease, individuals on dialysis, after surgery, after a physical trauma to the body, chronic poor dietary intake, and conditions that lead to muscle wasting. Calculation of protein needs under these circumstances is individualized and is typically estimated by a Registered Dietitian.

- If the individual is overweight or obese, protein goals should be based on an adjusted weight rather than the current weight. A Registered Dietitian can also assist with this calculation.

Are protein needs increased for regular exercisers?

Surprisingly, the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) report states that “ in view of the lack of compelling evidence to the contrary, no additional dietary protein is suggested for healthy adults undertaking resistance or endurance exercise” [3]. However, a review study found evidence that for anyone using resistance training with the intent to gain muscle mass, consuming extra protein may be beneficial, but the benefits max out at about 1.6g protein/Kg body weight/day [6].

Plant-based athletes should consult with a Sports Dietitian for specific guidance. A helpful article with general advice and resources on this topic can be found on the Vegetarian Resource Group website.

What are the signs and symptoms of protein deficiency?

Protein deficiency is not having enough protein in the diet to sustain normal body functions. It usually happens in the context of chronic caloric insufficiency, such as in populations suffering from starvation. But it can also develop due to prolonged illnesses or from an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa. End-stage-liver disease, individuals on dialysis, and certain types of cancer patients may also be at risk.

Some of the signs and symptoms of protein malnutrition include thinning of the skin and hair, the hair may stop growing, change color, and eventually fall out, brittle nails, muscle wasting, edema, weakened immune system as evidenced by increased infections, and when affecting children, leads to stunted physical growth [3, 7].

Health implications of protein excess

Protein adequacy is important, but beware of excess. Despite claims that a high protein diet is best for growth, weight loss, or that it is essential to develop strong muscles, there are adverse effects from eating too much protein, especially from animal sources. Some studies have found that infants fed formula can have an intake of up to 70 percent higher protein than breast-fed infants, but this extra protein does not seem to offer an additional benefit to those infants. In fact, the infants fed human milk exhibit better immune function and superior cognitive development than the formula-fed infants [8, 9].

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans mentions that more than half of the population is meeting or exceeding total protein foods recommendations, especially for meat, poultry, and eggs [10], which is an important link to consider in face of the high prevalence of chronic diseases in this country. Several studies point to animal-protein being associated with an increased risk for obesity, several types of cancer, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [11-13].

A high protein diet, especially from animal-sources, can also speed up the progression of chronic kidney disease on those who already suffer from this condition [14], and have a detrimental effect on bone health, as it leads to an increase calcium urinary loss [15].

What foods are rich in protein? Can I get enough protein on a plant-based diet?

The table below shows the sources of protein in foods based on the most common eating patterns.

| Diet Pattern | Dairy | Eggs | Fish | Poultry | Red Meat |

Beans, Lentils, Peas, Soy Products, Whole Grains, Vegetables, Nuts, Seeds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Vegetarian (aka, Omnivore) | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Semi-Vegetarian | Consume

at least |

any

1 time/month |

combination

but less than |

of animal

1 time/week |

foods | ✔︎ |

| Pesco-Vegetarian | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ||||

| Lacto-ovo-vegetarian | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | |||

| Strict Vegetarian (variations include vegan and WFPB*) | ✔︎ |

*Whole Food Plant-Based (a strict vegetarian diet that emphasizes unprocessed or minimally-processed plant-based foods)

Current scientific evidence indicates that protein intake is not a public health concern for adults and children over 4 years of age in the United States [16]. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics states that protein is not a concern on vegetarian diets either when caloric intakes are adequate [17]. They add that plant-based proteins can offer all the essential amino acids, when the diet meets the caloric needs of the individual, and when the diet is composed of a variety of foods.

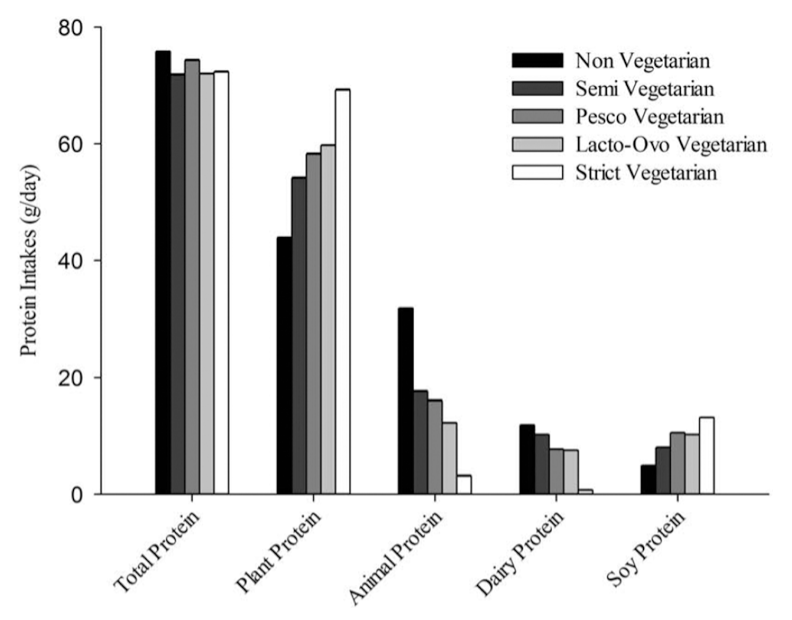

One of the many articles published by the Adventist Health Studies-2 from Loma Linda University looked at the dietary habits of 71,751 Seventh-Day Adventists, from data collected during five years, and found that there was no significant difference on total protein intake consumed at the various eating patterns. The significant difference was simply the source of protein consumed [18], as shown in the chart below.

Dietary mean protein intakes standardized to 2,000 kcal/day by dietary pattern in the Adventist Health Study 2. Adjustments were made for age, sex, and race. ∗Significant contrast (P<0.05) and a mean difference ≥20% when compared to nonvegetarian dietary pattern as the group of reference.

Another important finding from this study is that while the nonvegetarians had the highest intake of protein, they had the lowest intake of fiber, β-carotene, and magnesium, and the highest intakes of saturated, trans, arachidonic, and docosahexaenoic fatty acids, characterizing a more inflammatory diet that was associated with more cases of obesity and type 2 diabetes [18, 19]. On the other hand, the strict vegetarians met their protein needs, and had the lowest prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes, and the lowest incidence of cancer compared to the other dietary patterns [18-20].

Plant-based proteins have also been associated with a lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality when replacing animal-based proteins [21, 22].

Plant-based diets offer a variety of foods rich in protein. Some are unprocessed or minimally processed, and some are highly processed. The list below provides some suggestions on foods from each of these categories. An emphasis on unprocessed or minimally processed options will promote better health as those foods tend to be higher in fiber and lower in saturated fats, sodium, and added-sugars.

| Level of Processing | Food Sources |

|---|---|

| Unprocessed |

|

| Minimally Processed |

|

| Highly Processed |

|

* Fruits contain a negligible amount of protein, although they contribute with other important nutrients as discussed in other articles (See “Making Peace with Carbohydrates”)

Plant proteins are generally less digestible than animal proteins; however, digestibility can be improved through processing (such as sprouting, soaking, and fermenting) and preparation (such as boiling, roasting, and toasting).

Protein Content of Selected Plant-based Foods

| Food | Serving Size | Protein Amount (grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Tofu, raw, firm, prepared with calcium sulfate | ½ cup | 21.3 |

| Lentils, cooked | 1 cup | 17.9 |

| Pinto beans, cooked | 1 cup | 15.4 |

| Black beans, cooked | 1 cup | 14.5 |

| Edamame, cooked | ½ cup | 9.2 |

| Quinoa, cooked | 1 cup | 8.1 |

| Almonds | 1 oz | 6.0 |

| Brown rice, cooked | 1 cup | 5.6 |

| Sunflower seeds, roasted | ¼ cup | 4.9 |

| Corn, cooked | 1 cup | 4.5 |

| Broccoli, cooked | 1 cup | 3.7 |

| Peanut butter | 1 Tablespoon | 3.6 |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release April 2018.

How about the issue of “complete proteins”?

Even though most plant-based protein foods present some essential amino acids in a lower quantity than animal protein, different plant-based food groups complement each other. However, the terms complete and incomplete are obsolete and misleading in reference to plant protein as the experts point that when the diet provides adequate calories and a variety of plant-based foods there is no need to combine different plant proteins at each meal. This is because the body maintains a pool of amino acids – from all the foods consumed and from recycled proteins – which is used to provide for the body’s daily needs [23].

How about protein powders and shakes?

Commercial protein powders and shakes would be categorized under highly processed foods. Besides the fact that manufactures do not disclose the methods to extract and concentrate the protein in their products, if you read the Nutrition Facts on those products you will notice that often times they are enhanced with added-sugars or artificial sweeteners, oils, and preservatives. Therefore, they may not offer the same health benefits a whole-food offers. However, they may be useful in some circumstances:

- During sickness when the individual is not eating enough food and does not have the ability to buy and prepare more wholesome foods, and does not have the support of someone who could do it for him or her;

- At the early stages after bariatric surgery;

- To provide for the needs of certain athletes during training or competition if they choose this option versus a homemade preparation.

Does the Bible have anything to say about protein?

We know in the original diet God provided the foods that would provide all the nutrients for all His created beings to thrive, and that includes protein.

“And God said, “See, I have given you every herb that yields seed which is on the face of all the earth, and every tree whose fruit yields seed; to you it shall be for food.” Genesis 1:29

Numbers 11 also describes how God was displeased when the people complained about the manna He was providing for them in the desert and asked for meat. The psalmist adds

They willfully put God to the test by demanding the food they craved. They spoke against God; they said, “Can God really spread a table in the wilderness? True, he struck the rock, and water gushed out, streams flowed abundantly, but can he also give us bread? Can he supply meat for his people?” When the Lord heard them, he was furious. Psalm 78:18-21

Inspiration confirms that if we continue to follow God’s original plan, we will get all the necessary nutrients to provide for an abundant life.

One of the great errors that many insist upon is that muscular strength is dependent upon animal food. But the simple grains, fruits of the trees, and vegetables have all the nutritive properties necessary to make good blood. This a flesh diet cannot do. Letter 72, 1896.9

Summary

The truth about protein is that it is an important nutrient but it is one that is quite easy to get when we consume enough calories to maintain our ideal body weight and when our choices are from a variety of foods. It is also true that a total plant-based diet following these principles not only provides all the amino acids we need for good health, but it has shown to be superior than animal protein for health and longevity.

Here are some simple steps to ensure adequate protein intake on a daily basis:

- Consume beans, soybean products, lentils, or peas – preferably soaked overnight before cooking.

- Eat a handful (about ¼ cup) of nuts or seeds or incorporate them into your recipes;

- Make sure that about ¼ of your plate for at least two meals of the day have a protein-dense food option;

- Consume at least ½ of your plate for at least one meal of the day containing non-starchy vegetables;

- Make sure your grain choices are mostly from whole grains;

- Vary your food choices throughout the day and throughout the week, as much as possible.

When in doubt about your specific situation, consult with a Registered Dietitian.

Unprocessed and minimally processed plant-based protein-dense foods can be prepared in a variety of ways to maintain our joy of eating while providing for our body’s protein needs.

References

- Medicine, U.S.N.L.o. What are proteins and what do they do? ; Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/howgeneswork/protein/.

- St. John, T.M., Chapter 21 – Chronic Hepatitis, in Integrative Medicine (Fourth Edition), D. Rakel, Editor. 2018, Elsevier. p. 198-210.e5.

- Medicine, I.o., Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. 2005, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 1358.

- Parian, A.M., et al., Chapter 50 – Inflammatory Bowel Disease, in Integrative Medicine (Fourth Edition), D. Rakel, Editor. 2018, Elsevier. p. 501-516.e8.

- Kominiarek, M.A. and P. Rajan, Nutrition Recommendations in Pregnancy and Lactation. The Medical clinics of North America, 2016. 100(6): p. 1199-1215.

- Morton, R.W., et al., A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. Br J Sports Med, 2018. 52(6): p. 376-384.

- Semba, R.D., The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health. Annals of nutrition & metabolism, 2016. 69(2): p. 79-88.

- Anderson, J.W., B.M. Johnstone, and D.T. Remley, Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr, 1999. 70(4): p. 525-35.

- Oddy, W., The impact of breastmilk on infant and child health. Vol. 10. 2002: Australian Breastfeeding Association. 5–18.

- Agriculture., U.S.D.o.H.a.H.S.a.U.S.D.o. 2020 – 2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.9th Edition. 2020 December 2020; Available from: www.dietaryguidelines.gov/.

- Wolk, A., Potential health hazards of eating red meat. J Intern Med, 2017. 281(2): p. 106-122.

- Feskens, E.J., D. Sluik, and G.J. van Woudenbergh, Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Curr Diab Rep, 2013. 13(2): p. 298-306.

- Oellgaard, J., et al., Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) as a New Potential Therapeutic Target for Insulin Resistance and Cancer. Curr Pharm Des, 2017. 23(25): p. 3699-3712.

- Ko, G.J., et al., Dietary protein intake and chronic kidney disease. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care, 2017. 20(1): p. 77-85.

- Kerstetter, J.E., K.O. O’Brien, and K.L. Insogna, Dietary protein, calcium metabolism, and skeletal homeostasis revisited. Am J Clin Nutr, 2003. 78(3 Suppl): p. 584s-592s.

- (FDA), U.S.F.D.A. How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label. 03/11/2020; Available from: www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/how-understand-and-use-nutrition-facts-label.

- Melina, V., W. Craig, and S. Levin, Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet, 2016. 116(12): p. 1970-1980.

- Rizzo, N.S., et al., Nutrient profiles of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary patterns. J Acad Nutr Diet, 2013. 113(12): p. 1610-9.

- Tonstad, S., et al., Type of vegetarian diet, body weight, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2009. 32(5): p. 791-6.

- Tantamango-Bartley, Y., et al., Vegetarian diets and the incidence of cancer in a low-risk population. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2013. 22(2): p. 286-294.

- Fraser, G.E. and D.J. Shavlik, Ten Years of Life: Is It a Matter of Choice? Archives of Internal Medicine, 2001. 161(13): p. 1645-1652.

- Song, M., et al., Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2016. 176(10): p. 1453-1463.

- Marsh, K.A., E.A. Munn, and S.K. Baines, Protein and vegetarian diets. Med J Aust, 2013. 199(S4): p. S7-s10.

[…] Proteins (read article) […]

[…] High Source of Protein: pulses are one of the most convenient and versatile plant-based protein options. Studies show that those who eat plant-based protein instead of animal-based protein live longer and better [6, 7]. For more on specific information on plant-based proteins, see article on The Truth About Protein. […]

[…] For the recommended daily protein intake and foods that are rick on this nutrient see article The Truth About Protein. […]